'The Prada Principle' Vogue US August 1995

She started with a family company and an oddball idea—a nylon bag—then Miuccia Prada added shoes, clothes, and her own eccentric taste. The result, finds Katherine Betts, has become the invisible status symbol for the no-frills nineties.

Photographs: Ellen Von Unwerth

Hair: Sam McKnight

MUA: Mary Greenwell.

Fashion Editor: Grace Coddington

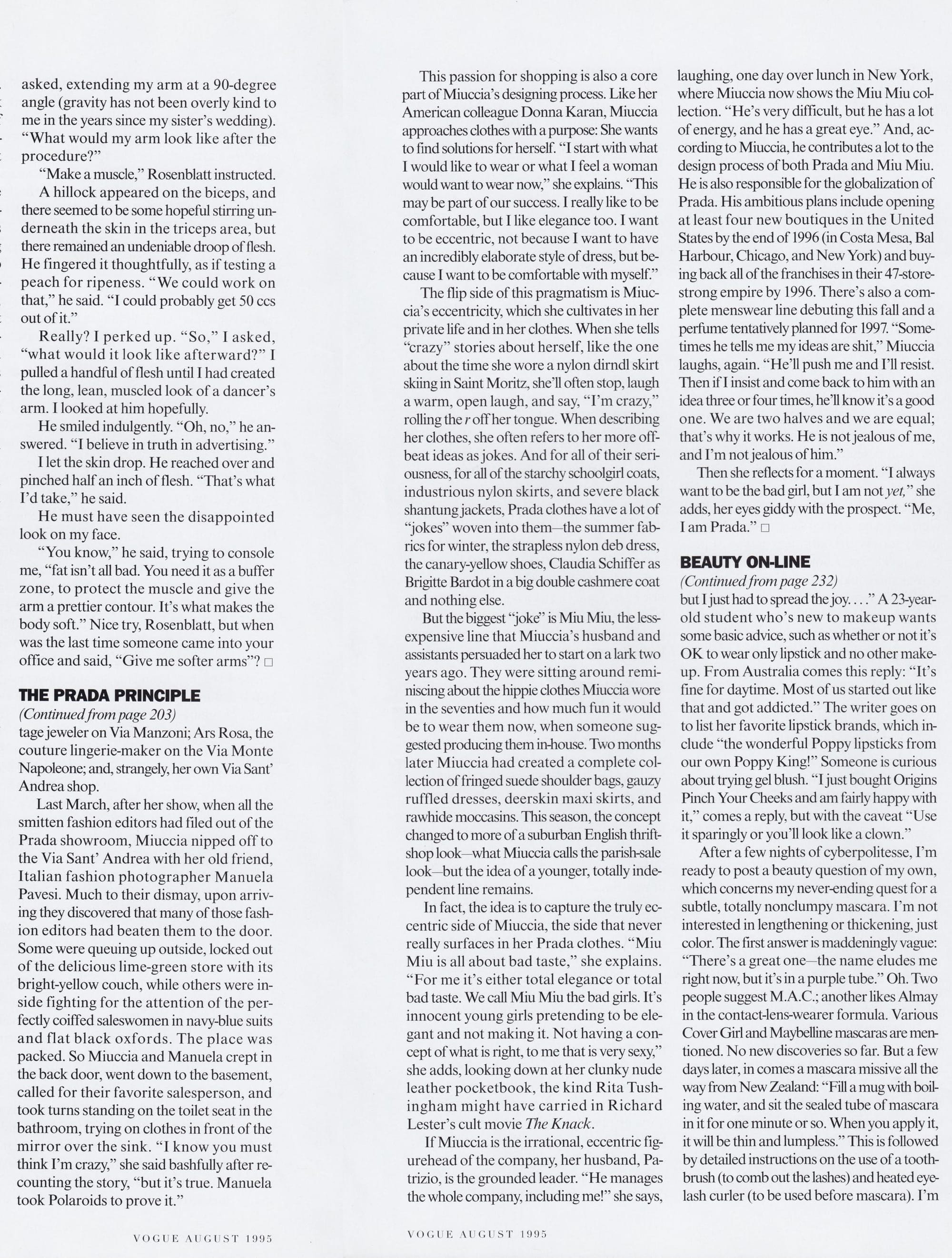

Donovan Leitch leads Kristen McMenamy in a last tango in Prada.

This page: The simple, fitted cut that has earned Prada a loyal following among a new generation of women. Wool and silk coatdress, about $1,500. Prada, NYC, Beverly Hills; Saks Fifth Avenue, Bala Cynwyd, PA; Harry B’s, Nashville.

Opposite page: Prada’s interpretation of the sleeveless shift has a dropped waist and pleated skirt, worn with a low-heeled patent leather boot. Sleeveless dress, about $790. Prada, NYC, Beverly Hills; Neiman Marcus, San Francisco.

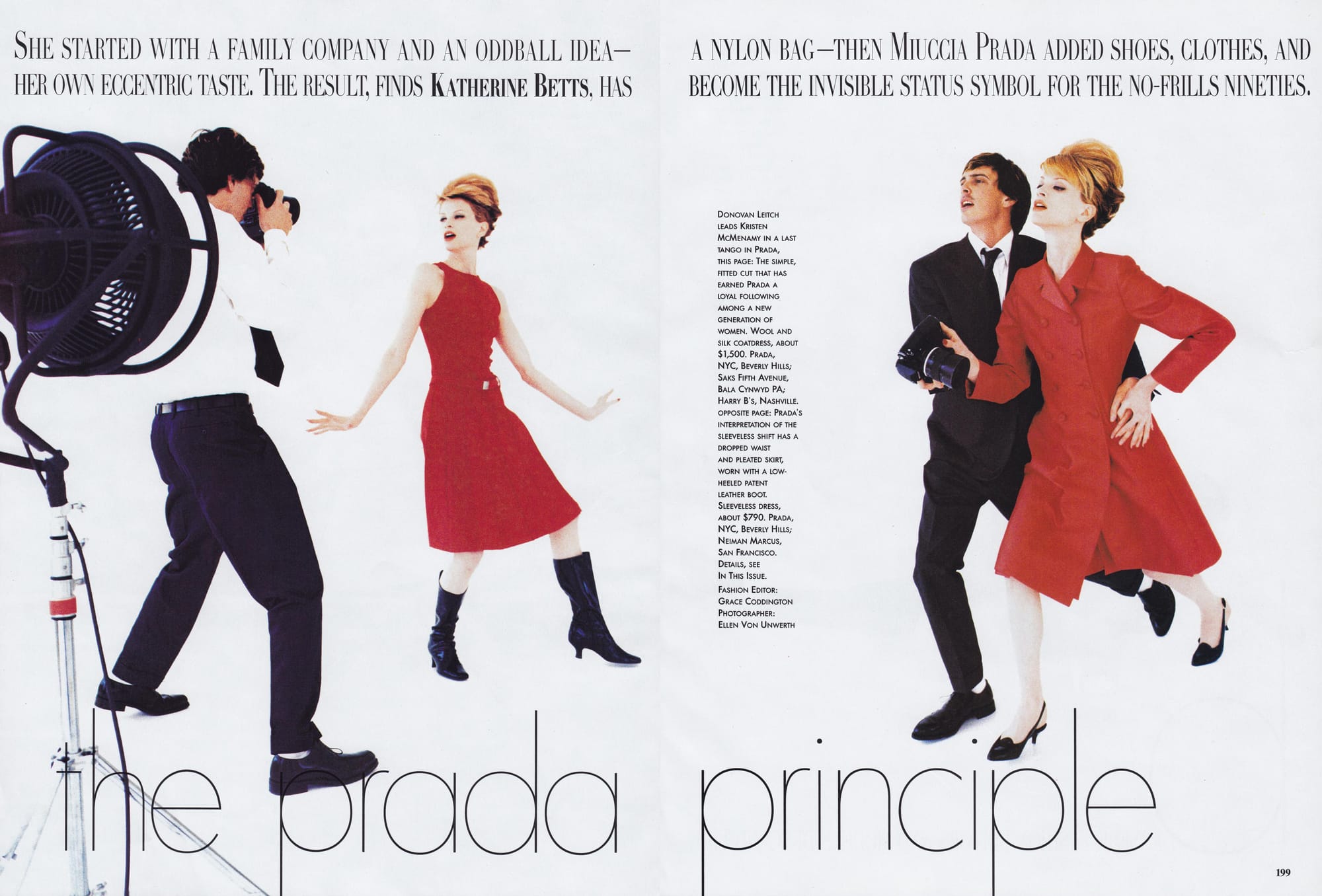

Berserk fashion editors and models descend like locusts and blindly devour every last shoe, dress, and skirt.

Taking matters into her own hands, this page, Prada relies on spartan design—rather than obvious logos—for her trademark. Standing firm: the Sabrina heel in two-tone red and black. Dress, about $840. Prada, NYC, Beverly Hills; Janet Brown, Port Washington, NY.

Opposite page: A close-up on the close-fitting Prada suit, here with a shapely jacket and matching skirt, is fast becoming the uniform for the working woman. Jacket, about $900, and skirt, about $660. Barneys New York; Prada, NYC, Beverly Hills; Linda Dresner, Birmingham, MI.

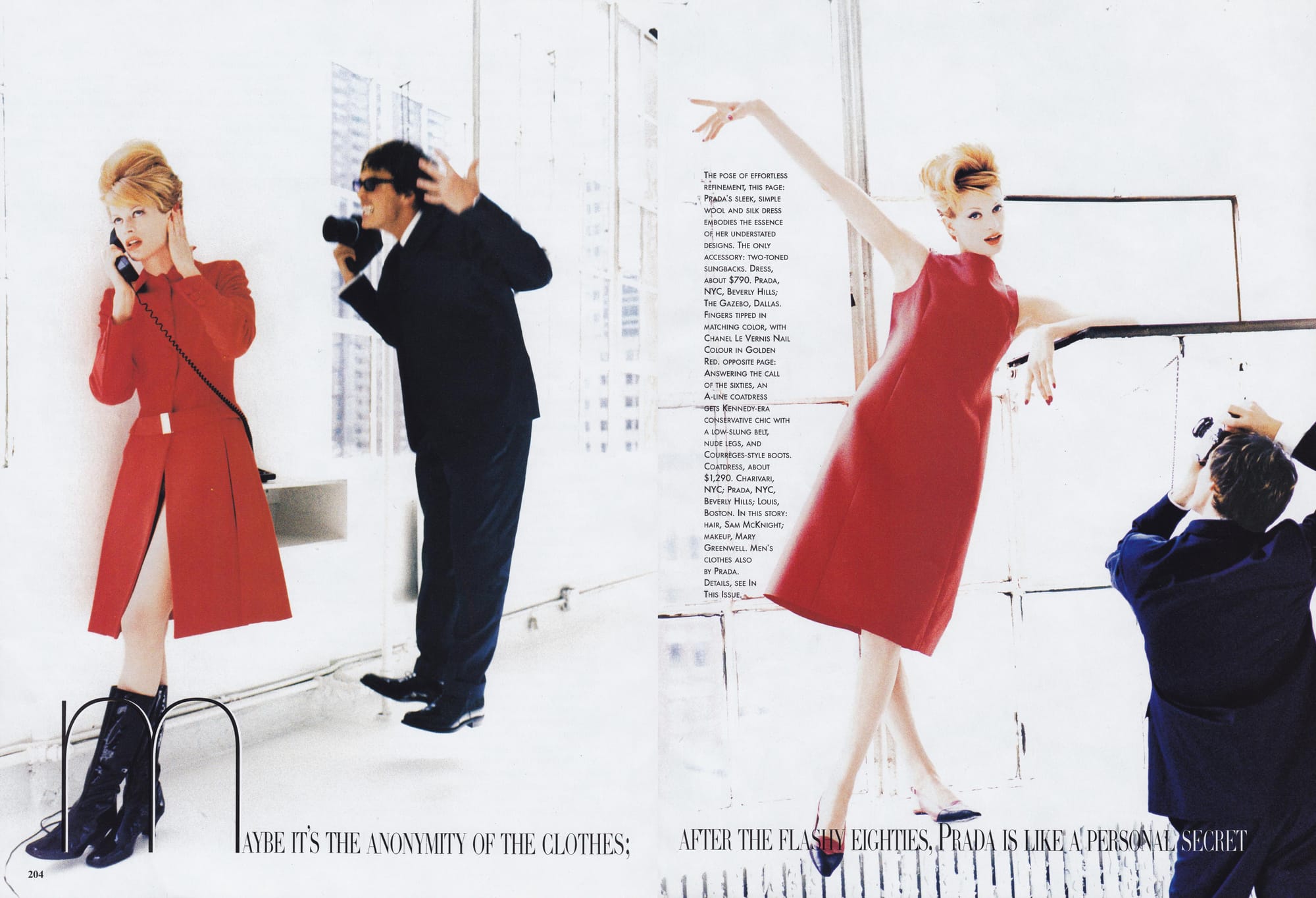

Maybe its the anonymity of the clothes; after the flashing eighties, Prada is like a personal secret.

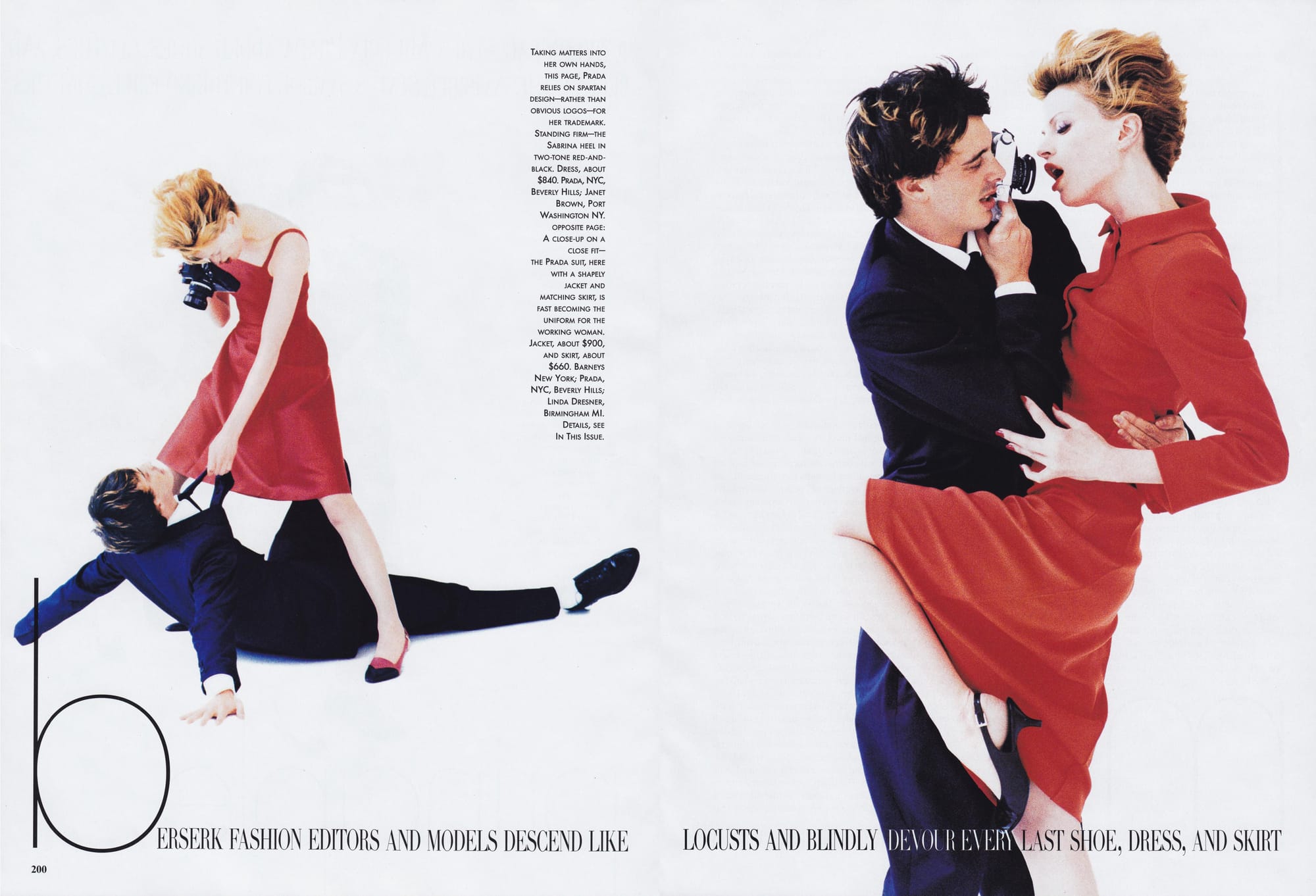

The Pose of Effortless Refinement

This page: Prada’s sleek, simple wool and silk dress embodies the essence of her understated designs. The only accessory: two-toned slingbacks. Dress, about $790. Prada, NYC, Beverly Hills; The Gazebo, Dallas. Fingers tipped in matching color, with Chanel Le Vernis nail colour in Golden Red.

Opposite page: Answering the call of the sixties, an A-line coatdress evokes Kennedy-era conservative chic with a low-slung belt, nude legs, and Courrèges-style boots. Coatdress, about $1,290. Charivari, NYC; Prada, NYC, Beverly Hills; Louis, Boston. Men’s clothes also by Prada.

Miuccia says the day she gets sick of buying clothes and dressing herself, she will quit the business.

It happened last March at the fall show of a major Italian fashion house. Two fat Milanese manufacturers sitting in the back row just could not contain themselves. Every time a supermodel stepped out onto the runway in a gossamer pastel slip dress or a fitted black military coat or a shiny nylon parka, the two men would inhale deeply, sigh, and finally, in unison, mutter a sort of fashion mantra for the nineties: “Prada. Prada. Pradissima.”

The fashion show they were watching was not Prada’s, though. It was that of another designer, who, like so many Italian, French, and American designers this season, could not escape the influence of 45-year-old Miuccia Prada and the family company she has seemingly effortlessly metamorphosed from a dusty luggagemaker to an international fashion symbol. Had they been at every fashion show last March, those manufacturers would have witnessed the infiltration of Prada’s cool, classic style on runways from Milan to Paris to New York. They would have been reciting that mantra in their sleep.

Prada’s story, of course, is not new. Anyone familiar with fashion today knows by heart the details of how Miuccia took over her grandfather Mario’s 82-year-old company at the age of 28 and turned it into a $210 million empire. They’ve heard repeatedly the anecdote about how, in 1985, she stitched Pocono nylon—the stuff military tents are made of—into an impossibly desirable tote bag. They’ve seen that bag, with its mix of modern fabric and old-fashioned fabrication, become the generic status symbol of this decade. They know the meaning of a discreet little metal triangle in a world of conspicuous interlocking Cs, Gs, and Fs.

They’ve heard about the berserk fashion editors and models descending each season like locusts on the Prada stores on Milan’s Via Sant’ Andrea and Galleria Vittorio Emanuele and blindly devouring every last bag, belt, and knee-length skirt before even checking into the Four Seasons Hotel. They’ve even read a bit about Miuccia, the shy, secretive woman who met her husband and business partner, Patrizio Bertelli, at a trade show when she spotted the bags his company manufactured and commented on his production standards.

But over the past year, the Prada phenomenon has become much more important than a local shopping frenzy; it’s become a lot bigger than a nylon bag. First there was the nylon bag; then the object of desire was a nylon parka; then Miuccia made shoes—plain black loafers and slick lace-up boots—that women could not live without. Suddenly, it’s a satin slip dress, a knee-length navy-blue nylon skirt, a narrow little stretchy camp belt, and an austere black gabardine military coat.

Come fall, fashion pages and trendy parties alike will be filled with sleeveless camel dresses, polished calf slingback shoes, and fitted orange-red radzimir coats. And yet the success of Prada seems inexplicable at a time when designers are struggling to define the terms of fashion’s future. What is the variable, for example, in the equation that adds up to $3,500 in sales per square foot in Prada boutiques when Hermès boutiques average only half that amount?

Maybe it’s the anonymity of the clothes, the fact that, after the flashy eighties, Prada is like a personal secret: only the person wearing it knows what it is. Unlike a Chanel or Armani suit or an Azzedine Alaïa dress or an Yves Saint Laurent jacket, the Prada silhouette is impossible to draw—there are no specific signatures like gold buttons or fluid fabrics or skintight knits or square shoulders. Yet the clothes still feel familiar. They feel like they could have come out of someone else’s closet—maybe even your own.

And hidden within that familiarity is an unthinkably modern element: a classic strapless dress, for example, looks like taffeta but is made of nylon. The success of Prada is partly due to all of the above, but mostly it’s due to Miuccia.

She is not a young “dauphin,” a Saint Laurent–size talent turning the fashion world topsy-turvy with a trapeze dress. She is not a master of shape and drape. In textbook terms, Miuccia Prada is not even a designer. She has no formal design training or technical skills, but she is smart enough to surround herself with a dream team of experts.

Hers is a postmodern approach to design: the Prada label is a collaborative effort by Miuccia, her husband, and several technical designers. Miu Miu, the company’s hip second line, is designed by Miuccia and a team of five designers. Accessories, shoes, and bags are created by another team. But the common denominator, the driving force behind the pristine Prada aesthetic, is wholly Miuccia. Nothing goes onto a runway or into production without her stamp of approval.

That stamp, the most important ingredient in this intangible success story, is based on a very specific and personal taste that Miuccia has cultivated over the course of her life. Most of it is derived from her experience growing up in the sixties and seventies in a rich industrial Milanese family (her father owned a company that made putting-green mowers) with a fashionable mother who inherited Milan’s most luxurious leather goods company.

Miuccia, the middle child of three, studied political science at Università Statale; she had a passion for mime, a membership in the Communist Party, and several Communist boyfriends.

Back in the seventies, when she was attending mime classes at the Piccolo Teatro and handing out leaflets at political demonstrations, Miuccia was ashamed of her interest in fashion (“too frivolous”). But today she is so entrenched in it that she recalls episodes of her life through clothes.

She remembers her early teens for the dresses her mother bought for her at Courrèges in Paris; her late teens for the hippie clothes she got at London’s ultratrendy shopping mecca, Biba, and the cool minimalist pieces she found at Jean Muir. In her early 20s, Miuccia discovered Yves Saint Laurent’s classic uniforms (her all-time favorites) and the world of French prêt-à-porter, including Kenzo’s famous Jungle Jap store in Paris.

She was wearing only vintage clothes, though, by her late 20s, when her mother retired and handed Prada’s reins over to her. Although she had some experience managing the family’s Galleria store, Miuccia’s only fashion knowledge came from her closet—and it’s still hanging there.

In her first few collections (she started with accessories and later added shoes and ready-to-wear to the Prada label), Miuccia’s clothes were classic, slightly awkward, and very reminiscent of the stiff, boxy styles her mother wore in the fifties and sixties. Although her designs have loosened up and become more streamlined, Miuccia still looks for inspiration in her closet in the early nineteenth-century building she shares with her mother, brother, aunt, husband, and two sons on Corso di Porta Romana.

The brilliant orange-red color of the radzimir coats and dresses in her fall collection came from a Hartnell couture coat she had when she was young. The white Courrèges-like ski pants and zipped-up A-line jackets that closed her fall show recall the gear Miuccia wore on vacation in St. Moritz as a kid. The pragmatic, austere, slightly military edge in all of her clothes has its roots in her Communist youth.

The sharp lines and strong uniformity also evoke the look of the Jean-Luc Godard movies she watched in the sixties. Every piece of Prada is a Proustian madeleine that Miuccia then processes through her aesthetic, fusing what she absorbs from the present with what she has absorbed in the past. This approach is what makes her clothes at once so precise and so free. She is not confined by a signature the way other designers are, and that’s a major factor in Prada’s current success.

“People recognize themselves in Prada clothes because they aren’t so distinctive,” says Marc Audibet, the French freelance designer who worked on the Prada collection for the past four years. “They have enough familiarity and anonymity to allow women to think the clothes make them look like themselves. Prada has the feeling of something that won’t change; it won’t surprise you.”

“She is timeless, and that’s what we’re all searching for. We don’t want to be caught in the moment of fashion anymore,” agrees Malcolm McLaren, the British music entrepreneur who put the Sex Pistols and punk fashion on the map in the seventies. “Miuccia is the complete opposite of a Christian Lacroix or a Jean Paul Gaultier because she has managed to jump out of fashion. Her clothes are not trying to make the big statement. They’re trying to be intelligent, and intelligence is glamorous now.”

“You’d love a teacher in Prada, wouldn’t you? You’d really want to sit down and talk to her. But imagine a teacher in Lacroix or Versace. Prada feels like a twenty-first-century Tiffany. It has that refinement, and yet it’s invisible.”

That refinement comes from the Italian side of Miuccia’s taste, which has nothing to do with the conservative Burberry raincoats, Timberland boots, and Ferragamo shoes that are so prevalent on the piazzas of Milan. It means that Miuccia likes traditional things like Smythson notebooks from London, stodgy couture fabrics like radzimir, and old-world Milanese restaurants like the hushed, red-velvet-lined Savini, where the ghosts of Maria Callas and Grace Kelly still linger.

But she also likes modern things like nylon, contemporary Italian abstract art, and Joe Colombo chairs. She mixes the old with the new, and everything around her reflects that quirky synthesis.

In the pared-down, heavy-duty industrial Prada studio and showroom on Milan’s Via Andrea Maffei, sexy women smoke cigarettes and answer phones in glassed-in booths worthy of garage attendants. Amid the poured concrete, linoleum, and whitewashed walls there will be a table covered in hand-sewn lace and laid out with arancia juice in crystal pitchers and panini sandwiches on silver platters.

There’s something quaint and yet hard-core about Miuccia’s world. Her taste is not “good”; she likes things to be slightly off. She likes bare legs in winter with heavy English tweed coats. She likes to take old-fashioned fabrics and make them modern with stretch or nylon.

“I like the wrong thing for the season, summer cotton for winter,” she explained one afternoon before her fall show, rifling through racks of clothes in the studio. “To me it’s the most eccentric thing you can do, but my husband thinks I’m crazy. It took me a month to convince the people in the factory that I wanted the fabric of a very heavy men’s coat for a skirt.”

On this particular day, she has been working with her staff of stylists, assistants, shoe designers, and merchandisers for hours, fitting models, eating panini, and proclaiming, lightheartedly, that a pair of pants is too long, a skirt too short. Yet Miuccia is hardly the designer as dictator; she is more the designer as sieve.

Members of her staff liken the experience of working with her to talking to a good friend about clothes. They call her by affectionate Italian nicknames like Miu Miu. But beneath her smiling eyes and soft Pre-Raphaelite face lurks great determination. She runs, never walks, across the studio, and even when she’s laughing, it’s clear that Miuccia is not a woman who does something against her will.

“She has a great softness,” says Audibet. “She’s very feminine but also very strong in character. She’s a real woman with a big personality.”

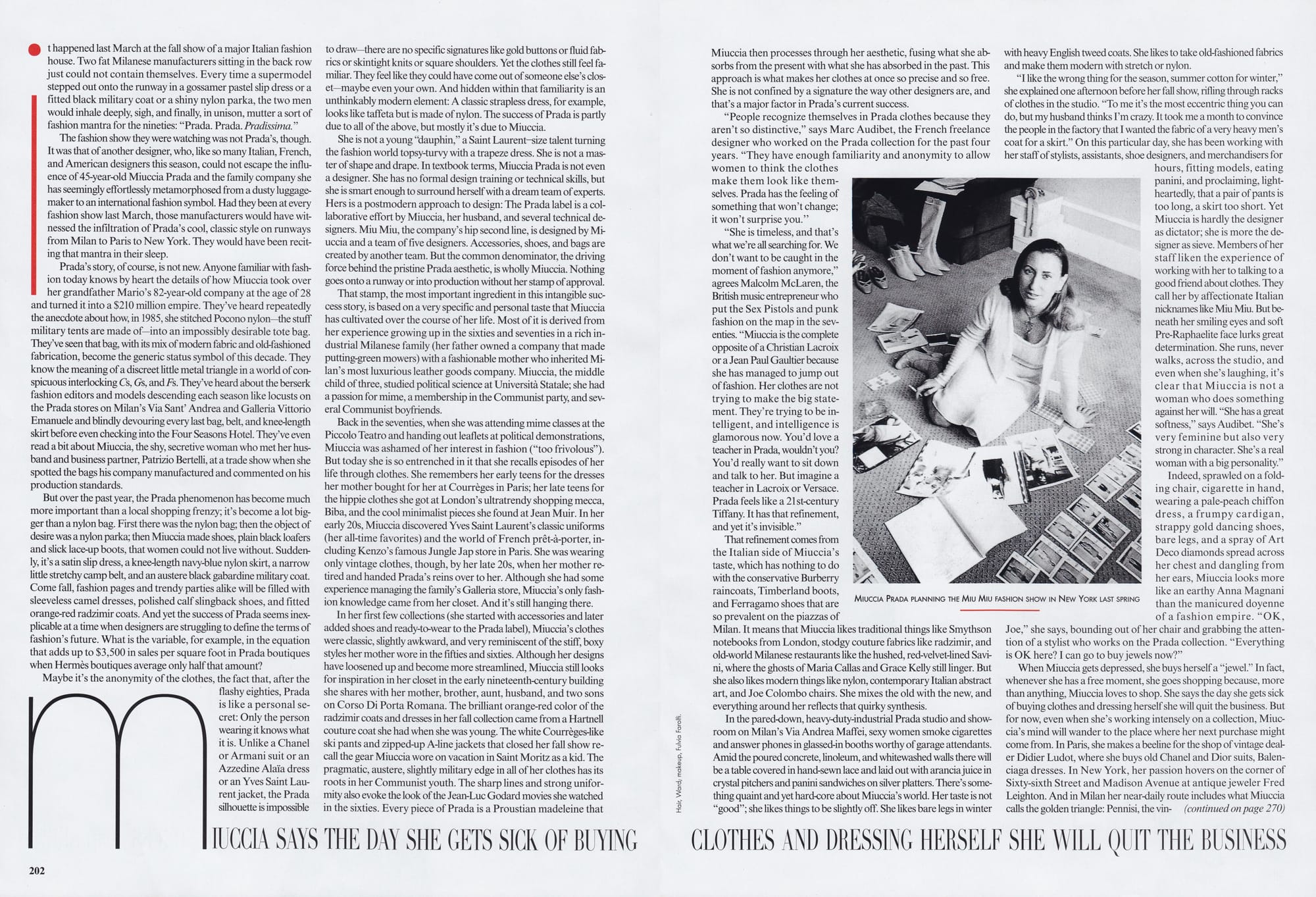

Indeed, sprawled on a folding chair, cigarette in hand, wearing a pale-peach chiffon dress, a frumpy cardigan, strappy gold dancing shoes, bare legs, and a spray of Art Deco diamonds spread across her chest and dangling from her ears, Miuccia looks more like an earthy Anna Magnani than the manicured doyenne of a fashion empire.

“Ok, Joe,” she says, bounding out of her chair and grabbing the attention of a stylist who works on the Prada collection. “Everything is Ok here? I can go buy jewels now?”

When Miuccia gets depressed, she buys herself a “jewel.” In fact, whenever she has a free moment, she goes shopping because, more than anything, Miuccia loves to shop. She says the day she gets sick of buying clothes and dressing herself she will quit the business.

But for now, even when she’s working intensely on a collection, Miuccia’s mind will wander to the place where her next purchase might come from. In Paris, she makes a beeline for the shop of vintage dealer Didier Ludot, where she buys old Chanel and Dior suits and Balenciaga dresses. In New York, her passion hovers on the corner of Sixty-sixth Street and Madison Avenue at antique jeweler Fred Leighton.

And in Milan her near-daily route includes what Miuccia calls the golden triangle: Pennisi, the vintage jeweler on Via Manzoni; Ars Rosa, the couture lingerie-maker on Via Monte Napoleone; and, strangely, her own Via Sant’ Andrea shop.

Last March, after her show, when all the smitten fashion editors had filed out of the Prada showroom, Miuccia nipped off to the Via Sant’ Andrea with her old friend, Italian fashion photographer Manuela Pavesi. Much to their dismay, upon arriving they discovered that many of those fashion editors had beaten them to the door.

Some were queuing up outside, locked out of the delicious lime-green store with its bright-yellow couch, while others were inside fighting for the attention of the perfectly coiffed saleswomen in navy-blue suits and flat black Oxfords. The place was packed.

So Miuccia and Manuela crept in the back door, went down to the basement, called for their favorite salesperson, and took turns standing on the toilet seat in the bathroom, trying on clothes in front of the mirror over the sink.

“I know you must think I’m crazy,” she said bashfully after recounting the story, “but it’s true. Manuela took Polaroids to prove it.”

This passion for shopping is also a core part of Miuccia’s designing process. Like her American colleague Donna Karan, Miuccia approaches clothes with a purpose: she wants to find solutions for herself.

“I start with what I would like to wear or what I feel a woman would want to wear now,” she explains. “This may be part of our success. I really like to be comfortable, but I like elegance too. I want to be eccentric, not because I want to have an incredibly elaborate style of dress, but because I want to be comfortable with myself.”

The flip side of this pragmatism is Miuccia’s eccentricity, which she cultivates in her private life and in her clothes. When she tells “crazy” stories about herself—like the one about the time she wore a nylon dirndl skirt skiing in St. Moritz—she’ll often stop, laugh a warm, open laugh, and say, “I’m crazy,” rolling the r off her tongue.

When describing her clothes, she often refers to her more offbeat ideas as jokes. And for all of their seriousness, for all of the starchy schoolgirl coats, industrious nylon skirts, and severe black shantung jackets, Prada clothes have a lot of “jokes” woven into them: the summer fabrics for winter, the strapless nylon deb dress, the canary-yellow shoes, Claudia Schiffer as Brigitte Bardot in a big double cashmere coat and nothing else.

But the biggest “joke” is Miu Miu, the less expensive line that Miuccia’s husband and assistants persuaded her to start on a lark two years ago. They were sitting around reminiscing about the hippie clothes Miuccia wore in the seventies and how much fun it would be to wear them now, when someone suggested producing them in-house.

Two months later Miuccia had created a complete collection of fringed suede shoulder bags, gauzy ruffled dresses, deerskin maxi skirts, and rawhide moccasins. This season, the concept changed to more of a suburban English thrift-shop look—what Miuccia calls the parish-sale look—but the idea of a younger, totally independent line remains.

In fact, the idea is to capture the truly eccentric side of Miuccia, the side that never really surfaces in her Prada clothes. “Miu Miu is all about bad taste,” she explains. “For me it’s either total elegance or total bad taste. We call Miu Miu the bad girls. It’s innocent young girls pretending to be elegant and not making it. Not having a concept of what is right, to me that is very sexy.”

She adds, looking down at her clunky nude leather pocketbook, the kind Rita Tushingham might have carried in Richard Lester’s cult movie The Knack.

If Miuccia is the irrational, eccentric figurehead of the company, her husband, Patrizio, is the grounded leader. “He manages the whole company, including me!” she says, laughing, one day over lunch in New York, where Miuccia now shows the Miu Miu collection.

“He’s very difficult, but he has a lot of energy, and he has a great eye.” And, according to Miuccia, he contributes a lot to the design process of both Prada and Miu Miu.

He is also responsible for the globalization of Prada. His ambitious plans include opening at least four new boutiques in the United States by the end of 1996 (in Costa Mesa, Bal Harbour, Chicago, and New York) and buying back all of the franchises in their 47-store-strong empire by 1996. There’s also a complete menswear line debuting this fall and a perfume tentatively planned for 1997.

“Sometimes he tells me my ideas are shit,” Miuccia laughs again. “He’ll push me and I’ll resist. Then if I insist and come back to him with an idea three or four times, he’ll know it’s a good one. We are two halves and we are equal; that’s why it works. He is not jealous of me, and I’m not jealous of him.”

Then she reflects for a moment. “I always want to be the bad girl, but I am not yet,” she adds, her eyes giddy with the prospect. “Me, I am Prada.”