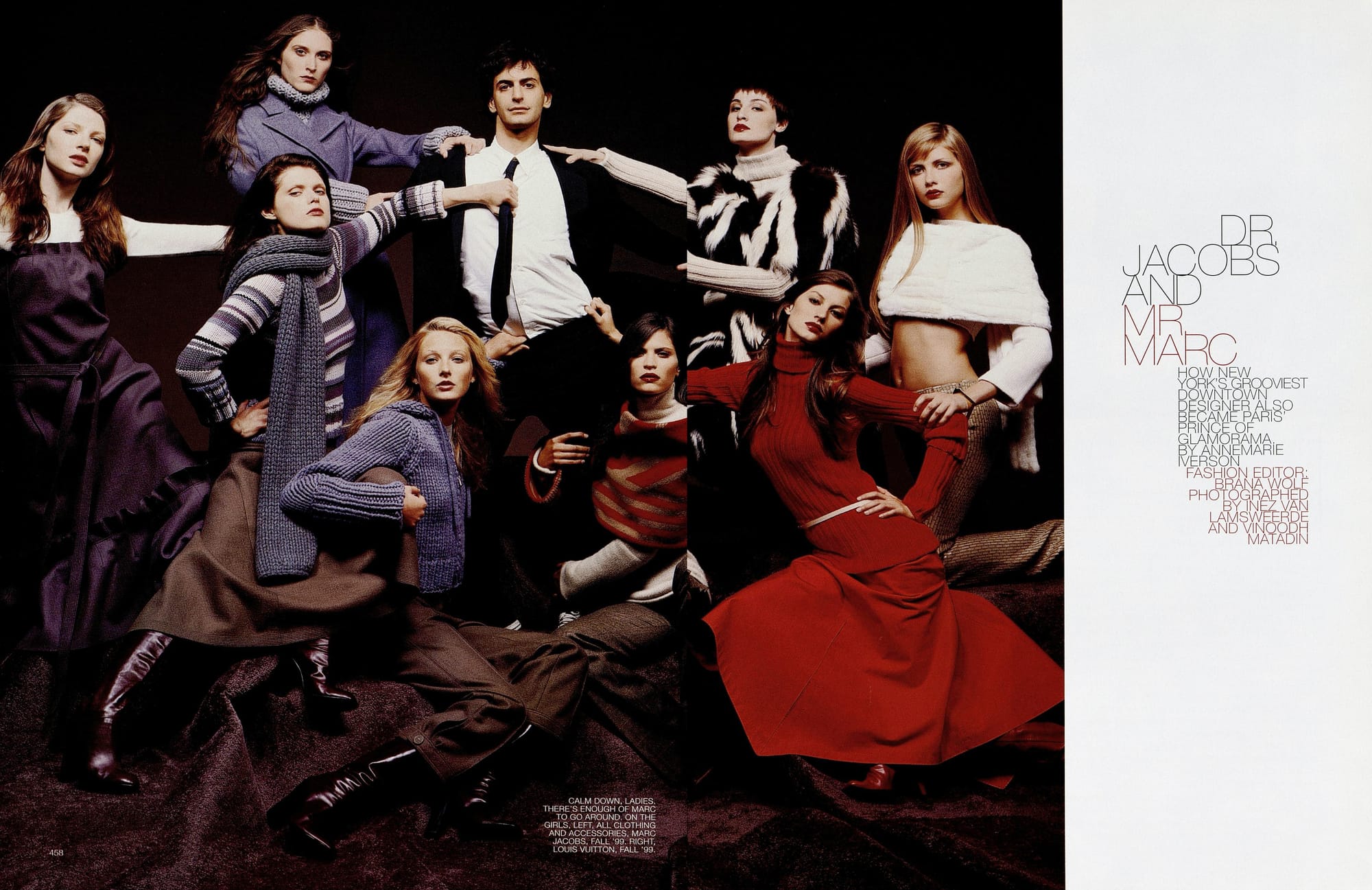

'Dr. Jacobs & Mr. Marc' - Harper's Bazaar September 1999

How New York's grooviest downtown designer also became Paris' Prince of Glamorama.

Fashion Editor: Brana Wolf

Photography: Inez Van Lamsweerde & Vinoodh Matadin

In the world according to Marc Jacobs, New York is understatedly cool; Paris, hot and sexy. New York is melancholy; Paris, optimistic. New York stands for clubbing, the latest restaurant and apartment-as-crash-pad; Paris means a chic arrondissement, a grown-up flat and signed deco pieces. Marc Jacobs' own label, headquartered in SoHo, is groovy-luxe, timeless American sportswear, while his Louis Vuitton ready-to-wear, based on the banks of the Seine, is Euro-flash sexy, logoed and universally recognizable.

After three years of jetting across the Atlantic, Jacobs seems to have struck the perfect balance between his two design realms, turning out a perfectly hip Marc Jacobs fall '99 collection in New York and then, three weeks later, a glamorous and heavily accessorized (read: near future financial success) Louis Vuitton line in Paris, a performance that had LVMH's Bernard Arnault-not one to reveal himself in this way-practically dancing on the runway.

"I guess I've really become Dr. Jacobs and Mr. Marc," admits the 36-year-old Jacobs of his compartmentalized existence. That this bad-boy design demon, who long aspired only to turn out groovy understated American clothes, has built a globally successful Vuitton fashion house in three short seasons surprises no one who's followed his career. That he's actually picked up and moved to Paris, however, does.

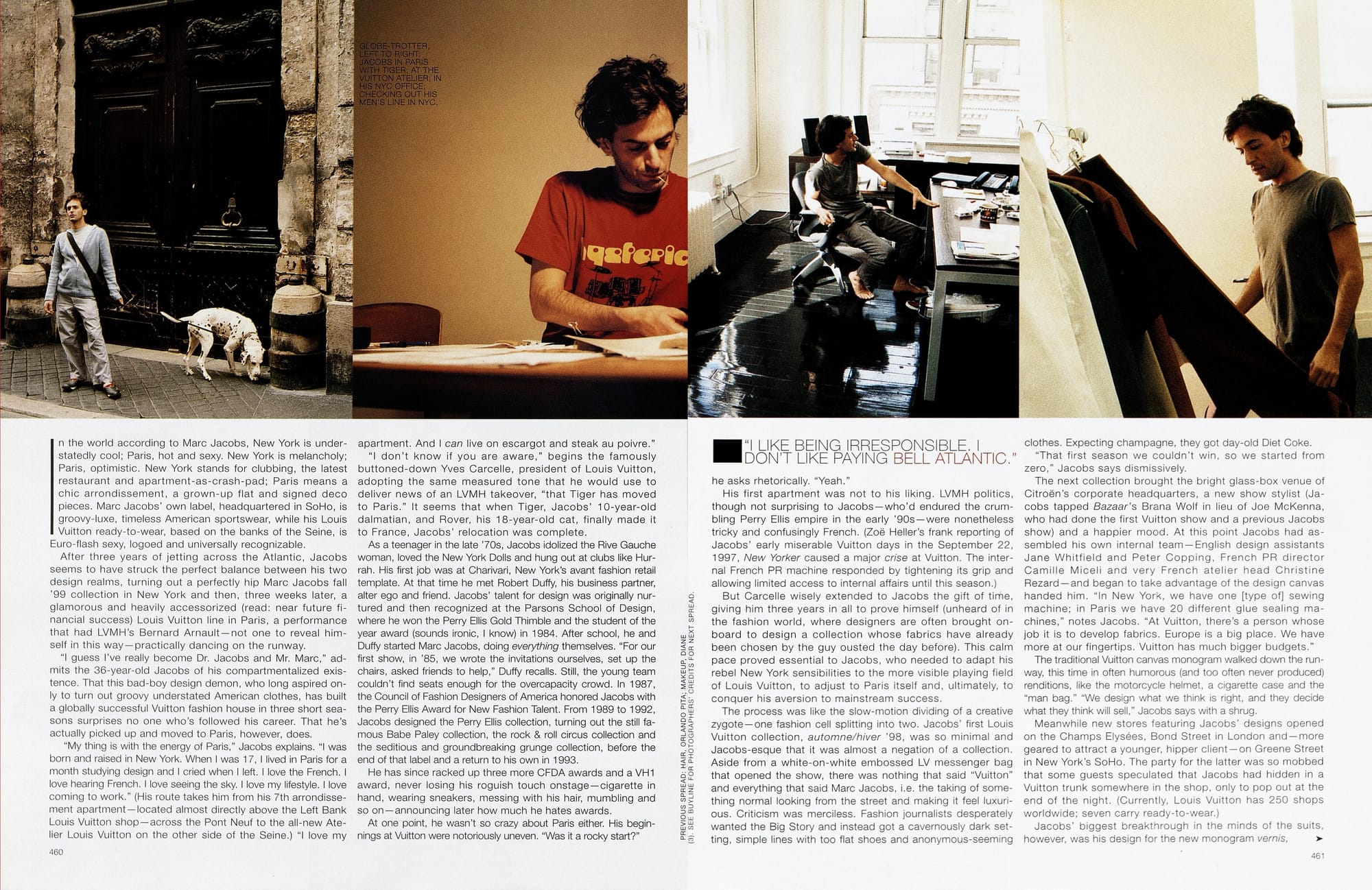

"My thing is with the energy of Paris," Jacobs explains. "I was born and raised in New York. When I was 17, I lived in Paris for a month studying design and I cried when I left. I love the French. I love hearing French. I love seeing the sky. I love my lifestyle. I love coming to work." (His route takes him from his 7th arrondissement apartment-located almost directly above the Left Bank Louis Vuitton shop-across the Pont Neuf to the all-new Atelier Louis Vuitton on the other side of the Seine.) "I love my apartment. And I can live on escargot and steak au poivre."

"I don't know if you are aware," begins the famously buttoned-down Yves Carcelle, president of Louis Vuitton, adopting the same measured tone that he would use to deliver news of an LVMH takeover, "that Tiger has moved to Paris." It seems that when Tiger, Jacobs' 10-year-old Dalmatian, and Rover, his 18-year-old cat, finally made it to France, Jacobs' relocation was complete.

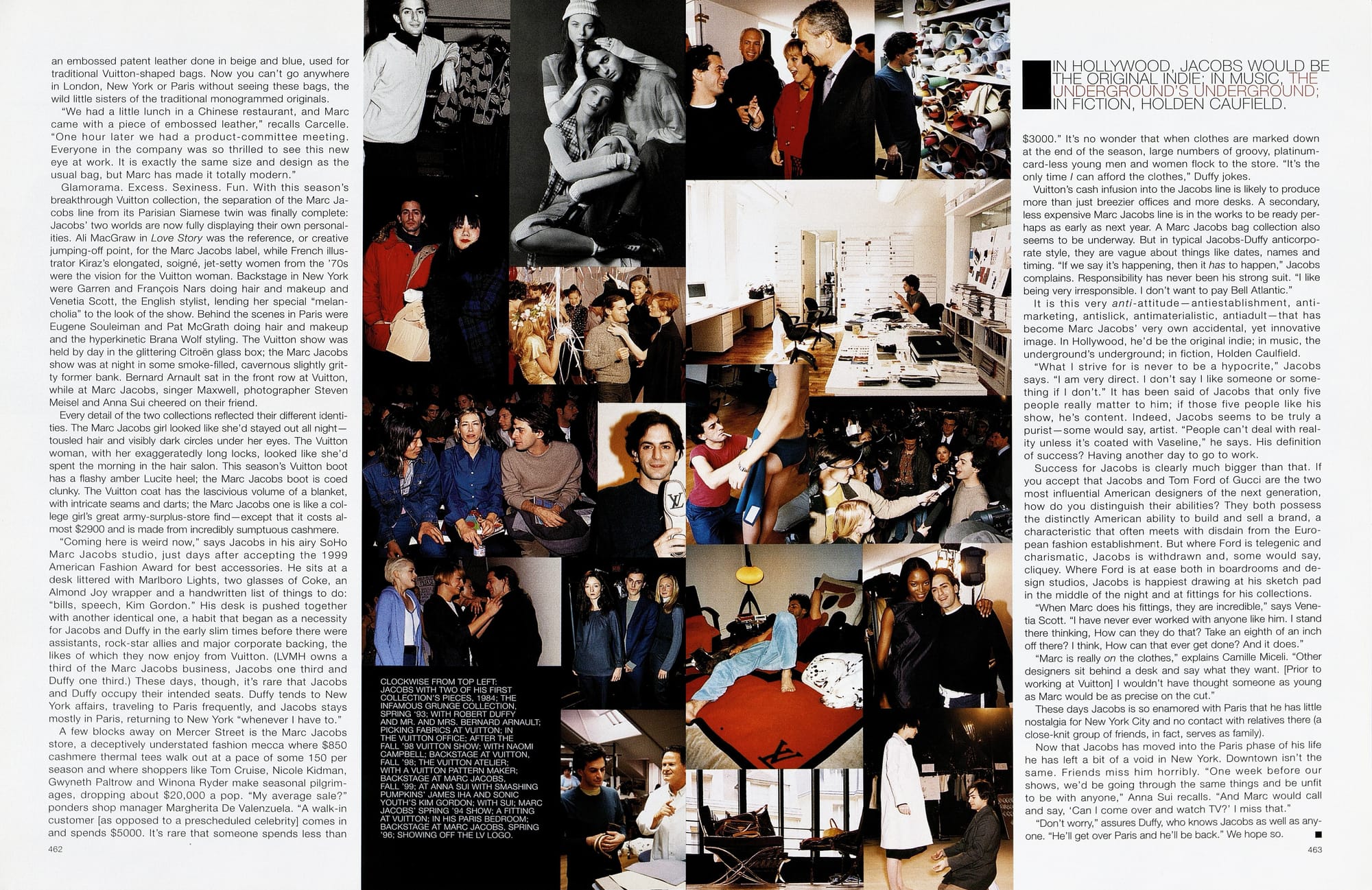

As a teenager in the late '70s, Jacobs idolized the Rive Gauche woman, loved the New York Dolls and hung out at clubs like Hurrah. His first job was at Charivari, New York's avant fashion retail template. At that time he met Robert Duffy, his business partner, alter ego and friend. Jacobs' talent for design was originally nurtured and then recognized at the Parsons School of Design, where he won the Perry Ellis Gold Thimble and the student of the year award (sounds ironic, I know) in 1984. After school, he and Duffy started Marc Jacobs, doing everything themselves. "For our first show, in '85, we wrote the invitations ourselves, set up the chairs, asked friends to help," Duffy recalls. Still, the young team couldn't find seats enough for the overcapacity crowd. In 1987, the Council of Fashion Designers of America honored Jacobs with the Perry Ellis Award for New Fashion Talent. From 1989 to 1992, Jacobs designed the Perry Ellis collection, turning out the still famous Babe Paley collection, the rock & roll circus collection and the seditious and groundbreaking grunge collection, before the end of that label and a return to his own in 1993.

He has since racked up three more CFDA awards and a VH1 award, never losing his roguish touch onstage-cigarette in hand, wearing sneakers, messing with his hair, mumbling and so on -announcing later how much he hates awards.

At one point, he wasn't so crazy about Paris either. His beginning at Vuitton were notoriously uneven. "Was it a rocky start?" he asks rhetorically. "Yeah."

His first apartment was not to his liking. LVMH politics, though not surprising to Jacobs —who'd endured the crumbling Perry Ellis empire in the early '90s—were nonetheless tricky and confusingly French. (Zoë Heller's frank reporting of Jacobs' early miserable Vuitton days in the September 22, 1997, New Yorker caused a major crise at Vuitton. The internal French PR machine responded by tightening its grip and allowing limited access to internal affairs until this season.)

But Carcelle wisely extended to Jacobs the gift of time, giving him three years in all to prove himself (unheard of in the fashion world, where designers are often brought onboard to design a collection whose fabrics have already been chosen by the guy ousted the day before). This calm pace proved essential to Jacobs, who needed to adapt his rebel New York sensibilities to the more visible playing field of Louis Vuitton, to adjust to Paris itself and, ultimately, to conquer his aversion to mainstream success.

The process was like the slow-motion dividing of a creative zygote —one fashion cell splitting into two. Jacobs' first Louis Vuitton collection, automne/hiver '98, was so minimal and Jacobs-esque that it was almost a negation of a collection.

Aside from a white-on-white embossed LV messenger bag that opened the show, there was nothing that said "Vuitton" and everything that said Marc Jacobs, i.e. the taking of something normal looking from the street and making it feel luxuri-ous. Criticism was merciless. Fashion journalists desperately wanted the Big Story and instead got a cavernously dark set-ting, simple lines with too flat shoes and anonymous seeming clothes. Expecting champagne, they got day-old Diet Coke.

"That first season we couldn't win, so we started from zero," Jacobs says dismissively.

The next collection brought the bright glass-box venue of Citroën's corporate headquarters, a new show stylist (Jacobs tapped Bazaar's Brana Wolf in lieu of Joe McKenna, who had done the first Vuitton show and a previous Jacobs show) and a happier mood. At this point Jacobs had assembled his own internal team-English design assistants Jane Whitfield and Peter Copping, French PR director Camille Miceli and very French atelier head Christine Rezard-and began to take advantage of the design canvas handed him. "In New York, we have one [type of] sewing machine; in Paris we have 20 different glue sealing ma-chines," notes Jacobs. "At Vuitton, there's a person whose job it is to develop fabrics. Europe is a big place. We have more at our fingertips. Vuitton has much bigger budgets."

The traditional Vuitton canvas monogram walked down the run-way, this time in often humorous (and too often never produced) renditions, like the motorcycle helmet, a cigarette case and the

"man bag." "We design what we think is right, and they decide what they think will sell," Jacobs says with a shrug.

Meanwhile new stores featuring Jacobs' designs opened on the Champs Elysées, Bond Street in London and - more geared to attract a younger, hipper client— on Greene Street in New York's SoHo. The party for the latter was so mobbed that some guests speculated that Jacobs had hidden in a Vuitton trunk somewhere in the shop, only to pop out at the end of the night. (Currently, Louis Vuitton has 250 shops worldwide; seven carry ready-to-wear.)

Jacobs' biggest breakthrough in the minds of the suits, an embossed patent leather done in beige and blue, used for traditional Vuitton-shaped bags. Now you can't go anywhere in London, New York or Paris without seeing these bags, the wild little sisters of the traditional monogrammed originals.

"We had a little lunch in a Chinese restaurant, and Marc came with a piece of embossed leather," recalls Carcelle. "One hour later we had a product-committee meeting. Everyone in the company was so thrilled to see this new eye at work. It is exactly the same size and design as the usual bag, but Marc has made it totally modern."

Glamorama. Excess. Sexiness. Fun. With this season's breakthrough Vuitton collection, the separation of the Marc Jacobs line from its Parisian Siamese twin was finally complete: Jacobs' two worlds are now fully displaying their own personalities. Ali MacGraw in Love Story was the reference, or creative jumping off point, for the Marc Jacobs label, while French illustrator Kiraz's elongated, soigné, jet-setty women from the '70s were the vision for the Vuitton woman. Backstage in New York were Garren and François Nars doing hair and makeup and Venetia Scott, the English stylist, lending her special "melancholia" to the look of the show. Behind the scenes in Paris were Eugene Souleiman and Pat McGrath doing hair and makeup and the hyperkinetic Brana Wolf styling. The Vuitton show was held by day in the glittering Citroën glass box; the Marc Jacobs show was at night in some smoke-filled, cavernous slightly gritty former bank. Bernard Arnault sat in the front row at Vuitton, while at Marc Jacobs, singer Maxwell, photographer Steven Meisel and Anna Sui cheered on their friend.

Every detail of the two collections reflected their different identities. The Marc Jacobs girl looked like she'd stayed out all night - tousled hair and visibly dark circles under her eyes. The Vuitton woman, with her exaggeratedly long locks, looked like she'd spent the morning in the hair salon. This season's Vuitton boot has a flashy amber Lucite heel; the Marc Jacobs boot is coed clunky. The Vuitton coat has the lascivious volume of a blanket, with intricate seams and darts; the Marc Jacobs one is like a college girl's great army-surplus-store find — except that it costs almost $2900 and is made from incredibly sumptuous cashmere.

"Coming here is weird now," says Jacobs in his airy SoHo Marc Jacobs studio, just days after accepting the 1999 American Fashion Award for best accessories. He sits at a desk littered with Marlboro Lights, two glasses of Coke, an Almond Joy wrapper and a handwritten list of things to do: "bills, speech, Kim Gordon." His desk is pushed together with another identical one, a habit that began as a necessity for Jacobs and Duffy in the early slim times before there were assistants, rockstar allies and major corporate backing, the likes of which they now enjoy from Vuitton. (LVMH owns a third of the Marc Jacobs business, Jacobs one third and Duffy one third.) These days, though, it's rare that Jacobs and Duffy occupy their intended seats. Duffy tends to New York affairs, traveling to Paris frequently, and Jacobs stays mostly in Paris, returning to New York "whenever I have to."

A few blocks away on Mercer Street is the Marc Jacobs store, a deceptively understated fashion mecca where $850 cashmere thermal tees walk out at a pace of some 150 per season and where shoppers like Tom Cruise, Nicole Kidman, Gwyneth Paltrow and Winona Ryder make seasonal pilgrim-ages, dropping about $20,000 a pop. "My average sale?" ponders shop manager Margherita De Valenzuela. "A walk-in customer [as opposed to a prescheduled celebrity] comes in and spends $5000. It's rare that someone spends less than $3000." It's no wonder that when clothes are marked down at the end of the season, large numbers of groovy, platinum-card-less young men and women flock to the store. "It's the only time / can afford the clothes," Duffy jokes.

Vuitton's cash infusion into the Jacobs line is likely to produce more than just breezier offices and more desks. A secondary, less expensive Marc Jacobs line is in the works to be ready perhaps as early as next year. A Marc Jacobs bag collection also seems to be underway. But in typical Jacobs-Duffy anticorpo-rate style, they are vague about things like dates, names and timing. "If we say it's happening, then it has to happen," Jacobs complains. Responsibility has never been his strong suit. "I like being very irresponsible. I don't want to pay Bell Atlantic."

It is this very anti-attitude — antiestablishment, anti-marketing, antislick, antimaterialistic, antiadult —that has become Marc Jacobs' very own accidental, yet innovative image. In Hollywood, he'd be the original indie; in music, the underground's underground; in fiction, Holden Caulfield

"What I strive for is never to be a hypocrite," Jacobs says. "I am very direct. I don't say I like someone or something if I don't." It has been said of Jacobs that only five people really matter to him; if those five people like his show, he's content. Indeed, Jacobs seems to be truly a purist-some would say, artist. "People can't deal with reality unless it's coated with Vaseline," he says. His definition of success? Having another day to go to work.

Success for Jacobs is clearly much bigger than that. If you accept that Jacobs and Tom Ford of Gucci are the two most influential American designers of the next generation, how do you distinguish their abilities? They both possess the distinctly American ability to build and sell a brand, a characteristic that often meets with disdain from the European fashion establishment. But where Ford is telegenic and charismatic, Jacobs is withdrawn and, some would say, cliquey. Where Ford is at ease both in boardrooms and design studios, Jacobs is happiest drawing at his sketch pad in the middle of the night and at fittings for his collections.

"When Marc does his fittings, they are incredible," says Venetia Scott. "I have never ever worked with anyone like him. I stand there thinking, How can they do that? Take an eighth of an inch off there? I think, How can that ever get done? And it does."

"Marc is really on the clothes," explains Camille Miceli. "Other designers sit behind a desk and say what they want. [Prior to working at Vuitton] I wouldn't have thought someone as young as Marc would be as precise on the cut."

These days Jacobs is so enamored with Paris that he has little nostalgia for New York City and no contact with relatives there (a close-knit group of friends, in fact, serves as family).

Now that Jacobs has moved into the Paris phase of his life he has left a bit of a void in New York. Downtown isn't the same. Friends miss him horribly. "One week before our shows, we'd be going through the same things and be unfit to be with anyone," Anna Sui recalls. "And Marc would call and say, 'Can I come over and watch TV?' I miss that."

"Don't worry," assures Duffy, who knows Jacobs as well as any-one. "He'll get over Paris and he'll be back." We hope so.