'Antwerp's Fashion Facets' - DNR December 1987

Antwerp’s Fashion Facets

By Alexander Lobrano

Some cities exert a minor claim on the world’s imagination, and Antwerp—an ancient and prosperous gemstone-trading port of half a million on the North Sea in Belgium—until recently was one of them. But occasionally, for the very reason that such a city is not as exhaustively worked by the world’s fashion media as New York or Paris or London, something really exciting and honestly unique happens in one of these off-stage places.

Enter Antwerp.

From seemingly out of the blue, three very talented and singular new menswear designers have attracted the spotlights of the world’s fashion press, and major retailers are quickly learning how to pronounce their names: Dirk Bikkembergs, Walter van Bierendonck, and Dries van Noten.

These men are half of the Antwerp Six, a loose confederation of young designers, all of whom studied fashion at various but overlapping times at the Academie, the venerable art school in Antwerp that the artist Rubens also attended. It was this concurrence of emerging and complementary talent—more than any distinctly local factor (aside from cheap rents)—that explains the sudden flowering of big-league talent.

“When we met, we all had different strengths and weaknesses, and we were inspired by one another,” says van Bierendonck. The designers also agree that the anonymity of Antwerp was an advantage. “We were spared having to make too many compromises too early,” Bikkembergs explains.

While these young Belgian menswear maestros had already visited Osaka to great acclaim on a government-sponsored trip and received eager, early coverage in a few French publications, the rest of the world discovered them with clamorous enthusiasm in London at the British Designer Menswear Show in March 1986. They’ve been gaining velocity ever since, scoring big this year at the Köln Fair and at Pitti Uomo.

Whether the stress of high visibility and the strains of commercial success will eventually cause the members of this intimate group to go their own ways, time alone will tell. They are generally frustrated by their dealings with stodgy local manufacturers, and the lure of Italy or the glamour of Paris may yet tempt one or more away from Antwerp. Wherever this trio may drift, however, it is likely that the creative bonhomie they share will keep them on course individually.

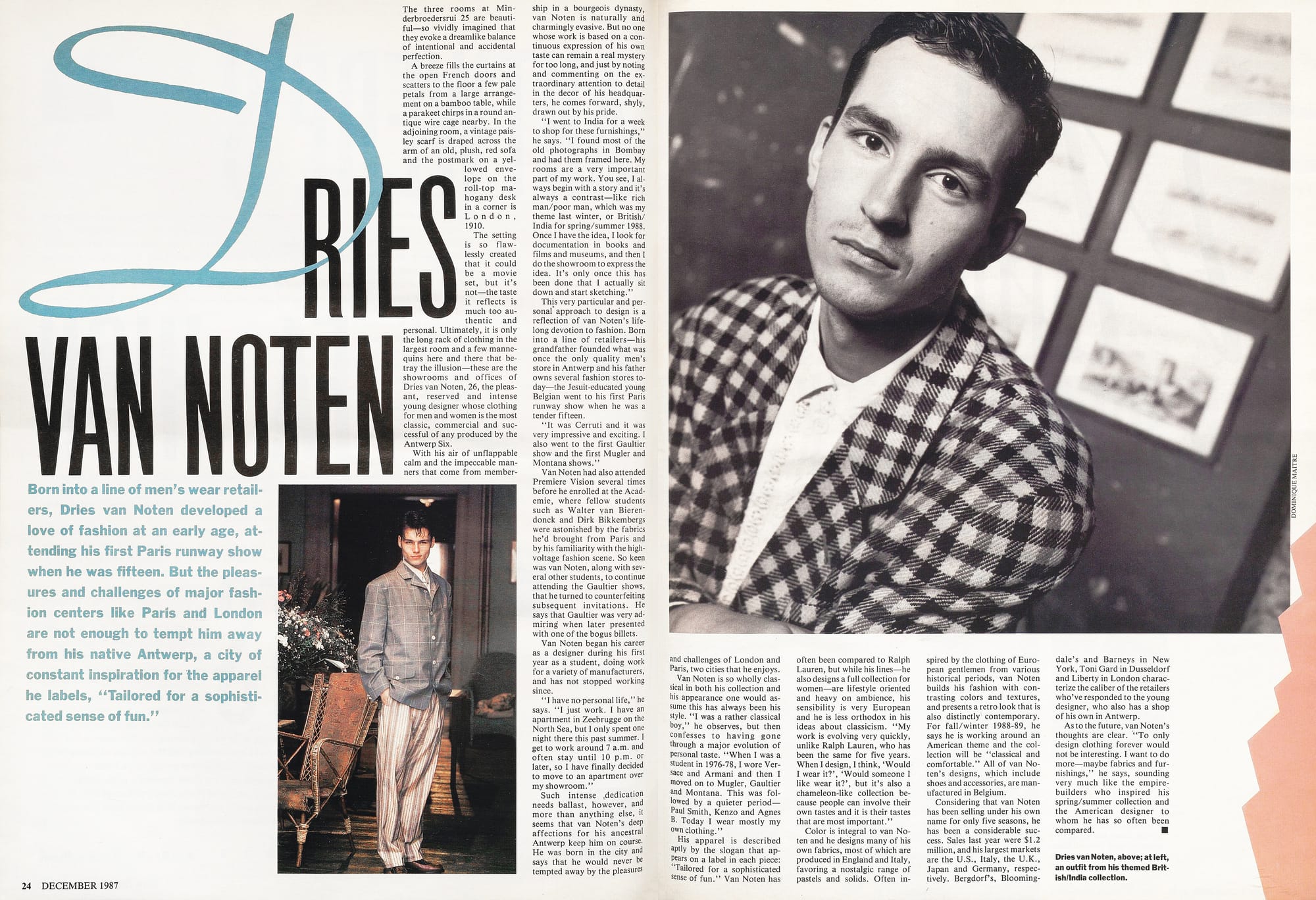

Dries Van Noten

Born into a line of menswear retailers, Dries van Noten developed a love of fashion at an early age, attending his first Paris runway show when he was fifteen. But the pleasures and challenges of major fashion centers like Paris and London are not enough to tempt him away from his native Antwerp, a city of constant inspiration for the apparel he labels “tailored for a sophisticated sense of fun.”

The three rooms at Minderbroedersrui 25 are beautiful—so vividly imagined that they evoke a dreamlike balance of intentional and accidental perfection.

A breeze fills the curtains at the open French doors and scatters to the floor a few pale petals from a large arrangement on a bamboo table, while a parakeet chirps in a round antique wire cage nearby. In the adjoining room, a vintage paisley scarf is draped across the arm of an old, plush red sofa, and the postmark on a yellowed envelope on the roll-top mahogany desk in a corner is London, 1910.

The setting is so flawlessly created that it could be a movie set, but it’s not—the taste it reflects is much too authentic and personal. Ultimately, it is only the long rack of clothing in the largest room and a few mannequins here and there that betray the illusion. These are the showrooms and offices of Dries van Noten, 26, the pleasant, reserved, and intense young designer whose clothing for men and women is the most classic, commercial, and successful of any produced by the Antwerp Six.

With his air of unflappable calm and the impeccable manners that come from membership in a bourgeois dynasty, van Noten is naturally and charmingly evasive. But no one whose work is based on a continuous expression of his own taste can remain a real mystery for too long, and just by noting and commenting on the extraordinary attention to detail in the décor of his headquarters, he comes forward shyly, drawn out by his pride.

“I went to India for a week to shop for these furnishings,” he says. “I found most of the old photographs in Bombay and had them framed here. My rooms are a very important part of my work. You see, I always begin with a story, and it’s always a contrast—like rich man/poor man, which was my theme last winter, or British/India for spring/summer 1988. Once I have the idea, I look for documentation in books and films and museums, and then I do the showroom to express the idea. It’s only once this has been done that I actually sit down and start sketching.”

This very particular and personal approach to design is a reflection of van Noten’s lifelong devotion to fashion. Born into a line of retailers—his grandfather founded what was once the only quality men’s store in Antwerp, and his father owns several fashion stores today—the Jesuit-educated young Belgian went to his first Paris runway show when he was a tender fifteen.

“It was Cerruti, and it was very impressive and exciting. I also went to the first Gaultier show and the first Mugler and Montana shows.”

Van Noten had also attended Première Vision several times before he enrolled at the Academie, where fellow students such as Walter van Bierendonck and Dirk Bikkembergs were astonished by the fabrics he’d brought from Paris and by his familiarity with the high-voltage fashion scene. So keen was van Noten, along with several other students, to continue attending the Gaultier shows that he turned to counterfeiting subsequent invitations. He says that Gaultier was very admiring when later presented with one of the bogus billets.

Van Noten began his career as a designer during his first year as a student, doing work for a variety of manufacturers, and has not stopped working since.

“I have no personal life,” he says. “I just work. I have an apartment in Zeebrugge on the North Sea, but I only spent one night there this past summer. I get to work around 7 a.m. and often stay until 10 p.m. or later, so I have finally decided to move to an apartment over my showroom.”

Such intense dedication needs ballast, however, and more than anything else, it seems that van Noten’s deep affections for his ancestral Antwerp keep him on course. He was born in the city and says that he would never be tempted away by the pleasures and challenges of London and Paris, two cities that he enjoys.

Van Noten is so wholly classical in both his collections and his appearance one would assume this has always been his style. “I was a rather classical boy,” he observes, but then confesses to having gone through a major evolution of personal taste.

“When I was a student in 1976–78, I wore Versace and Armani, and then I moved on to Mugler, Gaultier, and Montana. This was followed by a quieter period—Paul Smith, Kenzo, and Agnès B. Today I wear mostly my own clothing.”

His apparel is described aptly by the slogan that appears on a label in each piece: “Tailored for a sophisticated sense of fun.” Van Noten has often been compared to Ralph Lauren, but while his lines—he also designs a full collection for women—are lifestyle-oriented and heavy on ambience, his sensibility is very European, and he is less orthodox in his ideas about classicism.

“My work is evolving very quickly, unlike Ralph Lauren, who has been the same for five years. When I design, I think, ‘Would I wear it?’ ‘Would someone I like wear it?’ But it’s also a chameleon-like collection because people can involve their own tastes, and it is their tastes that are most important.”

Color is integral to van Noten, and he designs many of his own fabrics, most of which are produced in England and Italy, favoring a nostalgic range of pastels and solids. Often inspired by the clothing of European gentlemen from various historical periods, van Noten builds his fashion with contrasting colors and textures and presents a retro look that is also distinctly contemporary.

For fall/winter 1988–89, he says he is working around an American theme, and the collection will be “classical and comfortable.” All of van Noten’s designs, which include shoes and accessories, are manufactured in Belgium.

Considering that van Noten has been selling under his own name for only five seasons, he has been a considerable success. Sales last year were $1.2 million, and his largest markets are the U.S., Italy, the U.K., Japan, and Germany, respectively. Bergdorf Goodman’s, Bloomingdale’s, and Barneys in New York; Toni Gard in Düsseldorf; and Liberty in London characterize the caliber of the retailers who’ve responded to the young designer, who also has a shop of his own in Antwerp.

As to the future, van Noten’s thoughts are clear. “To only design clothing forever would not be interesting. I want to do more—maybe fabrics and furnishings,” he says, sounding very much like the empire-builders who inspired his spring/summer collection and the American designer to whom he has so often been compared.

Dries van Noten, above; at left, an outfit from his themed British/India collection.

Walter Van Beirendonck

Walter van Bierendonck’s designs, which are as arresting as his physical presence, are not for the fainthearted. But looks can be deceiving—and just as this designer tempers his aggressive appearance with an amiable soft-spokenness, he cuts his clothes with just enough seriousness to get them noticed by the world’s retailers.

The English buyer, a strawberry blonde, thinks she’s made a mistake. “He’s down there? Down these steps?” The steep white staircase before her is bathed in red light, and the song “Blue Velvet” is playing below. The approach to Walter van Bierendonck’s showroom is, depending on your point of view, intriguing or alarming—and the same might be said of the clothing on display in the three rooms below—but the consensus is running very much in the young designer’s favor.

The sight of van Bierendonck, 31, does little to reassure the quailing Brit. His appearance is, in his own words, “aggressive.”

To greet press and buyers one afternoon during the recent Antwerp fashion week, he is wearing long earrings made of antique coins, and the long hair on the top of his head—the sides are almost shaved—is pulled back and secured with two big clips. His dog, an English bull terrier named Sado (as in sado-masochism), sits at his feet in the small, spotlighted showroom.

“For a lot of people, I’m a strange person,” van Bierendonck says with a grin, “but it’s just a bourgeois reaction to the way that I look.” This is not a political statement, but an observation about the power of clothing in shaping the way that we perceive each other—a subject that fascinates the amiable, soft-spoken designer.

In fact, the gap between what you might expect van Bierendonck to be like and the way he really is—gentle, earnest, friendly—cannot fail to prick your curiosity. What, for example, is the message of his very extreme and personal clothing?

“It’s not premeditated,” he says, toying with a small, nubbed black rubber disc, which is, it turns out, a nipple appliqué to be used on one of his sweatshirts. “I just do it. I work from within my imagination, and much of what I do expresses things that are going on in my life. For this collection, I thought about The Flintstones, the Masai tribe of Africa, and Jules Verne, but I don’t know where, exactly, these ideas come from.”

He does say, however, that he loves movies and television, and as a Belgian he has the widest selection of television shows in Western Europe, with over twenty different channels broadcasting programs from all over the world.

Do not think that the variously nourished and completely unfettered imagination that sustains van Bierendonck’s design is a flighty figment of fashion. His current collection is funded by commercial work that he does for big manufacturers like Bartsons, and there was little in his early life that encouraged a creative career. His father runs a garage in the village twelve miles from Antwerp where he grew up, and van Bierendonck says, “I had a rather complex youth with a lot of problems. I always wanted to express myself, and when I decided I wanted to go to art school, my parents opposed it, so I lost three or four years.”

Finally he prevailed, and he enrolled at the Academie in Antwerp with the idea of doing something with jewelry—Antwerp is one of the most important diamond-cutting and -dealing cities in the world. Before long, he discovered the fashion curriculum and knew immediately that it was what he’d been looking for.

After school, he did a brief stint in New York City, which he loves, and then, unable to find work in the U.S., returned to Antwerp. He showed his first collection, for summer, in September 1982, and—as he is habitually precise about his themes—it was based on sado-masochism, horses, and erotica artist Allen Jones. Following collections have grown from such diverse concepts as Hiawatha Meets Custer, Bad Baby Boys, and Daredevil Daddy.

Lively, outrageous, fearless—run-all describe van Bierendonck’s work, but it’s also serious. While he refuses to bend to commercial pressures, this designer is seasoned enough to adapt to the different reality of getting his clothing into stores around the world. This season he’s launched a line of commercial knits decorated with cheeky graphics—dinosaurs, pistols, a safe-sex insignia, and his own first name—as a way of increasing sales and making himself better known among the young men who are his market.

The rest of the season is based around handknits, most of which are produced by his sister and several friends, and a small collection of clothing. Everything is made in Belgium, and prototypes of all his clothing are sewn by nuns at a local convent. In the near future, van Bierendonck plans to do jeans and shoes.

And after so much hard work—in addition to doing his own collection and his freelance design work, he is an instructor at the Academie—business is starting to move. Browns and Midas in London, Ichi Ni San in Glasgow, shops in Paris and Hamburg, and stores all over Belgium and Holland carry him. And after making his American debut at Soadadae in Dallas, he’s hoping that the U.S. will start wanting more from Belgium than waffles.

Though total sales are in the range of several hundred thousand dollars, this has happened within only one year. Van Bierendonck, who thus far has financed himself entirely with loans and his own earnings, is understandably wary of growing too quickly. He says that he’d love to have a little more time to watch favorite films in the large nightmare-of-kitsch apartment where he lives with Dirk van Saene, another of the Antwerp Six.

But having learned how to fashion—and sell—the fruits of his fecund imagination, such unproductive free time seems an unlikely luxury.

Walter van Bierendonck, at left; at top and above, Bierendonck’s menswear (featuring his pet bull terrier, Sado), and the designer’s showroom in Antwerp.

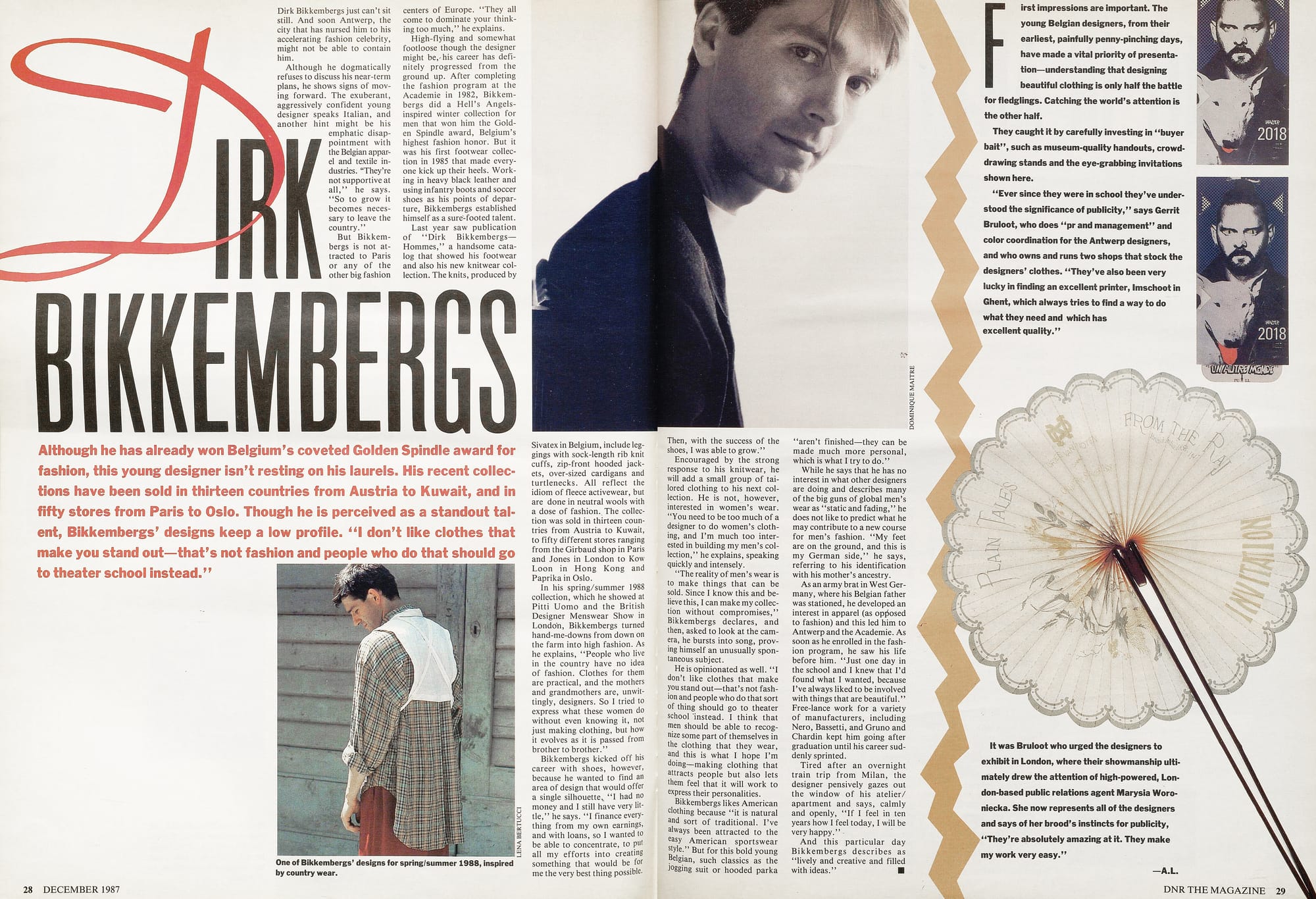

Dirk Bikkembergs

Although he has already won Belgium’s coveted Golden Spindle award for fashion, this young designer isn’t resting on his laurels. His recent collections have been sold in thirteen countries, from Austria to Kuwait, and in fifty stores, from Paris to Oslo. Though he is perceived as a standout talent, Bikkembergs’ designs keep a low profile. “I don’t like clothes that make you stand out—that’s not fashion, and people who do that should go to theater school instead.”

Dirk Bikkembergs just can’t sit still. And soon Antwerp, the city that has nursed him to his accelerating fashion celebrity, might not be able to contain him.

Although he dogmatically refuses to discuss his near-term plans, he shows signs of moving forward. The exuberant, aggressively confident young designer speaks Italian, and another hint might be his emphatic disappointment with the Belgian apparel and textile industries.

“They’re not supportive at all,” he says. “So to grow it becomes necessary to leave the country.”

But Bikkembergs is not attracted to Paris or any of the other big fashion centers of Europe. “They all come to dominate your thinking too much,” he explains.

High-flying and somewhat footloose though the designer might be, his career has definitely progressed from the ground up. After completing the fashion program at the Academie in 1982, Bikkembergs did a Hell’s Angels–inspired winter collection for men that won him the Golden Spindle award, Belgium’s highest fashion honor. But it was his first footwear collection in 1985 that made everyone kick up their heels.

Working in heavy black leather and using infantry boots and soccer shoes as his points of departure, Bikkembergs established himself as a sure-footed talent. Last year saw publication of Dirk Bikkembergs Hommes, a handsome catalog that showed his footwear and also his new knitwear collection.

The knits, produced by Sivatex in Belgium, include leggings with sock-length rib-knit cuffs, zip-front hooded jackets, oversized cardigans, and turtlenecks. All reflect the idiom of fleece activewear, but are done in neutral wools with a dose of fashion. The collection was sold in thirteen countries, from Austria to Kuwait, to fifty different stores ranging from the Girbaud shop in Paris and Jones in London to Kow Loon in Hong Kong and Paprika in Oslo.

In his spring/summer 1988 collection, which he showed at Pitti Uomo and the British Designer Menswear Show in London, Bikkembergs turned hand-me-downs from down on the farm into high fashion. As he explains:

“People who live in the country have no idea of fashion. Clothes for them are practical, and the mothers and grandmothers are, unwittingly, designers. So I tried to express what these women do without even knowing it—not just making clothing, but how it evolves as it is passed from brother to brother.”

Bikkembergs kicked off his career with shoes, however, because he wanted to find an area of design that would offer a single silhouette.

“I had no money and I still have very little,” he says. “I finance everything from my own earnings and with loans, so I wanted to be able to concentrate, to put all my efforts into creating something that would be for me the very best thing possible. Then, with the success of the shoes, I was able to grow.”

Encouraged by the strong response to his knitwear, he will add a small group of tailored clothing to his next collection. He is not, however, interested in womenswear.

“You need to be too much of a designer to do women’s clothing, and I’m much too interested in building my men’s collection,” he explains, speaking quickly and intensely.

“The reality of menswear is to make things that can be sold. Since I know this and believe this, I can make my collection without compromises.”

Asked to look at the camera, he bursts into song, proving himself an unusually spontaneous subject.

He is opinionated as well.

“I don’t like clothes that make you stand out—that’s not fashion, and people who do that sort of thing should go to theater school instead. I think that men should be able to recognize some part of themselves in the clothing that they wear, and this is what I hope I’m doing—making clothing that attracts people but also lets them feel that it will work to express their personalities.”

Bikkembergs likes American clothing because “it is natural and sort of traditional. I’ve always been attracted to the easy American sportswear style.” But for this bold young Belgian, such classics as the jogging suit or hooded parka “aren’t finished—they can be made much more personal, which is what I try to do.”

While he says that he has no interest in what other designers are doing and describes many of the big guns of global menswear as “static and fading,” he does not like to predict what he may contribute to a new course for men’s fashion.

“My feet are on the ground, and this is my German side,” he says, referring to his identification with his mother’s ancestry.

As an army brat in West Germany, where his Belgian father was stationed, he developed an interest in apparel (as opposed to fashion), and this led him to Antwerp and the Academie. As soon as he enrolled in the fashion program, he saw his life before him.

“Just one day in the school and I knew that I’d found what I wanted, because I’ve always liked to be involved with things that are beautiful.”

Freelance work for a variety of manufacturers, including Nero, Bassetti, and Grune and Chardin, kept him going after graduation until his career suddenly sprinted.

Tired after an overnight train trip from Milan, the designer pensively gazes out the window of his atelier/apartment and says calmly and openly, “If I feel in ten years how I feel today, I will be very happy.”

And this particular day, Bikkembergs describes as “lively and creative and filled with ideas.”

One of Bikkembergs’ designs for spring/summer 1988, inspired by country wear.

First impressions are important. The young Belgian designers, from their earliest, painfully penny-pinching days, have made a vital priority of presentation—understanding that designing beautiful clothing is only half the battle for fledglings. Catching the world’s attention is the other half.

They caught it by carefully investing in “buyer bait,” such as museum-quality handouts, crowd-drawing stands, and the eye-grabbing invitations shown here.

“Ever since they were in school, they’ve understood the significance of publicity,” says Gerrit Bruloot, who does “PR and management” and color coordination for the Antwerp designers, and who owns and runs two shops that stock the designers’ clothes. “They’ve also been very lucky in finding an excellent printer, Imschoot in Ghent, which always tries to find a way to do what they need and which has excellent quality.”

It was Bruloot who urged the designers to exhibit in London, where their showmanship ultimately drew the attention of high-powered, London-based public relations agent Marysia Woroniecka. She now represents all of the designers and says of her brood’s instincts for publicity, “They’re absolutely amazing at it. They make my work very easy. - A.L.

Afoot In Antwerp

Though it may be the astonishing cluster of talented young designers who first draw you to Antwerp, you will quickly see that the charms of the city itself more than merit a visit. As is true of many of the world’s favorite—and much larger—cities, Antwerp is complex and multifaceted, with a low-key cosmopolitan spirit that makes everyone welcome.

From the busy port area, where you might see a U.S. Navy ship and a Russian tanker docked at a discreet distance from one another, to the diamond district, with its introverted and almost feudal atmosphere of obsessive security and secrecy, the city contains a variety of harmonious contrasts.

The broad-minded, international outlook dates back to the Middle Ages, when Antwerp became established as one of the great trading centers of Europe. The wealth created by the city’s commerce generated patrons for great artists such as Peter Paul Rubens, who worked here.

And so it is the unself-conscious mélange of these historic qualities—plus low rents for large, attractive apartments and the esteemed Academie—that have recently made Antwerp a favored destination for trendy, footloose young Europeans. - A.L.

Restaurants

Here, as elsewhere in Belgium, moules, or mussels, are a favorite dish, and Antwerpians scarf down big steaming buckets of them along with platters of frites. What the locals call witloof (known to us as endive) is another native specialty and arrives at the table in a variety of toothsome guises, as do croquettes—among the best of which are cheese and shrimp. Wherever you pull a chair up to the table here, you’re likely to eat very well indeed.

Try Diaghilev (Maalderijstraat 1, tel. 2341868), five minutes from the Antwerp Cathedral, for lunch. The ambience is dreamy Belle Époque, prices are low, and thick steaks in mushroom cream sauce or expertly grilled sole are delicious and bracing fare for a busy afternoon—or an idle one—in a city where everyone walks everywhere.

Pottenbrug (Minderbroedersrui 38, tel. 2315147), right in the heart of designer country, is the kind of place you wish was right around the corner from every hotel you’ve ever stayed in. The culinary theme is fresh and eclectically international. Platters of perfectly grilled prawns served with lemon-pepper sauce and large salads will delight seafood lovers, and daily specials—such as roast lamb and moussaka—are expertly seasoned and prepared. The house wines are well-chosen French vintages at good prices, and save room for homemade desserts such as tarte Tatin with crème fraîche.

Hotels

While the Theater Hotel (Arenbergstraat 30, tel. 2311720) and the Empire Hotel (Appelmansstraat 31, tel. 2314755), both part of the Belgian-based Alfa hotel chain, offer standard-issue comfort, Antwerp does have one of the finest and most luxurious hotels in Western Europe: the Hotel Rosier (Rosier 21–23, tel. 2312497).

This charming and exclusive old inn is owned and run by antique dealers, and its public rooms are exquisitely furnished with some of their favorite pieces. Centrally located and featuring an intimate, lovingly tended private garden, you’ll know within minutes of arriving why the Rosier has counted the likes of Marlene Dietrich and Mick Jagger among its guests.

After Hours

Thanks to a tax code that has protected the country’s many local breweries from international purveyors of standardized suds, Belgium is famous for its beers, and the many lively cafés of Antwerp are perfect places to sample them.

The Spiegelbeeld Café, just behind the Grote Markt downtown, is the trendiest spot in town to enjoy brews, attracting a young, fashion-oriented crowd that doesn’t ever want the party to end. The décor is antique wrecking-ball style, with half the ceiling deliberately demolished and old wooden pull-down theater seats lining the wall in front of the bar and a platform in back. The crowd is friendly and widely English-speaking.

To catch a glimpse of the bawdy life of those on shore leave—and to experience a Europe you might otherwise know only from old films—head to Café Bevern on K. Plantin, down on the waterfront. The cast in this small, lively club could keep a novelist busy for years, as they dance and carouse to the jolly music of a huge, wall-mounted, pastel neon-lit automatic oompah band with organ.

Museums

With its long, proud history and wealth, Antwerp has many wonderful museums. The must-sees are the Koninklijk Museum Voor Schone Kunsten (Royal Fine Arts Museum) at Leopold de Waelplaats 1-9, and the Rubenshuis at Wapper 9.

Before entering the Koninklijk, take a stroll through the side streets nearby—they are filled with extravagantly whimsical Art Deco and Art Nouveau buildings. Plan to spend at least an hour in the museum, which houses one of the world’s great collections of Flemish and Dutch paintings. Canvases by Rubens, Rembrandt, and Breughel are just a few of the treasures you’ll find.

The Rubenshuis, built in 1610, is the discreetly and successfully restored house of Peter Paul Rubens. Beyond his paintings, it offers an interesting glimpse into bourgeois life in the 17th century.

Shops

For a city of its size, Antwerp has a surprising array of forward-thinking specialty stores, as well as boutiques from Versace, Ferre, and Yamamoto.

To see the Antwerp designers on the rack, visit Closing Date, at Korte Gasthuisstraat 15. This small shop carries both van Bierendonck and Bikkembergs, along with a selection of British designers such as Body Map, Nick Coleman, John Flett, and Katharine Hamnett.

Dries van Noten has his own store at Nieuwe Gaanderij 63, located in the mall at Huidevettersstraat 38, where his imaginatively decorated windows are a crowd-pleasing attraction.