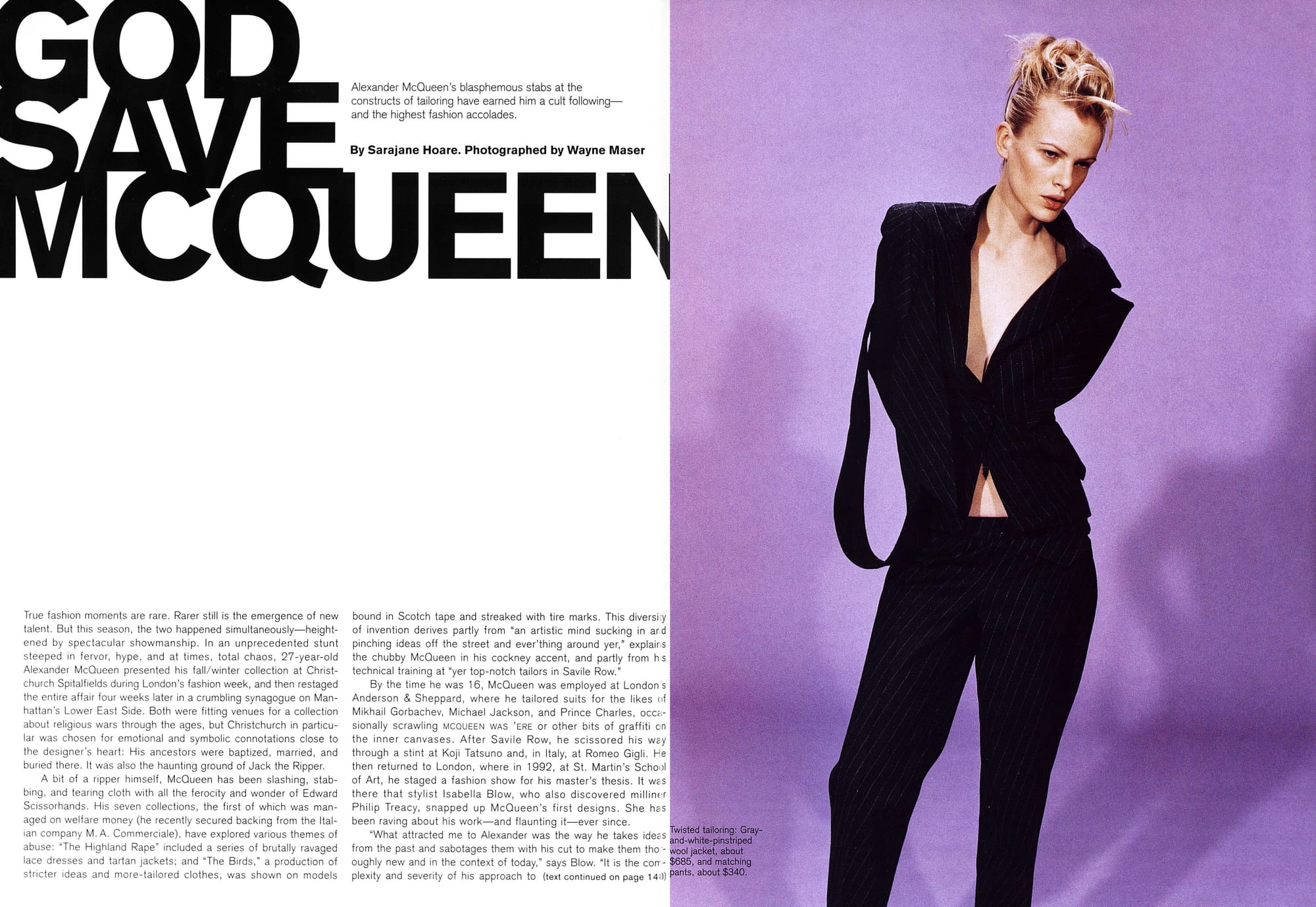

'God Save McQueen' - Harper's Bazaar June 1996

True fashion moments are rare. Rarer still is the emergence of new talent. But this season, the two happened simultaneously—heightened by spectacular showmanship. In an unprecedented stunt steeped in fervor, hype, and at times, total chaos, 27-year-old Alexander McQueen presented his fall/winter collection at Christchurch Spitalfields during London’s fashion week, and then restaged the entire affair four weeks later in a crumbling synagogue on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Both were fitting venues for a collection about religious wars through the ages, but Christchurch in particular was chosen for emotional and symbolic connotations close to the designer’s heart: His ancestors were baptized, married, and buried there. It was also the haunting ground of Jack the Ripper.

A bit of a ripper himself, McQueen has been slashing, stabbbing, and tearing cloth with all the ferocity and wonder of Edward Scissorhands. His seven collections, the first of which was managed on welfare money (he recently secured backing from the Italian company M. A. Commerciale), have explored various themes of abuse: "The Highland Rape" included a series of brutally ravaged lace dresses and tartan jackets; and "The Birds," a production of stricter ideas and more-tailored clothes, was shown on models bound in Scotch tape and streaked with tire marks. This diversity of invention derives partly from “an artistic mind sucking in and pinching ideas off the street and ever’thing around yer," explains the chubby McQueen in his cockney accent, and partly from his technical training at "yer top-notch tailors in Savile Row."

By the time he was 16, McQueen was employed at London's Anderson & Sheppard, where he tailored suits for the likes of Mikhail Gorbachev, Michael Jackson, and Prince Charles, occasionally scrawling McQueen was 'ere or other bits of graffiti on the inner canvases. After Savile Row, he scissored his way through a stint at Koji Tatsuno and, in Italy, at Romeo Gigli. He then returned to London, where in 1992, at St. Martin's School of Art, he staged a fashion show for his master's thesis. It was there that stylist Isabella Blow, who also discovered milliner Philip Treacy, snapped up McQueen's first designs. She has been raving about his work—and flaunting it-ever since.

"What attracted me to Alexander was the way he takes ideas from the past and sabotages them with his cut to make them thoroughly new and in the context of today," says Blow. "It is the complexity and severity of his approach to cut that makes him so modern. He is like a Peeping Tom in the way he slits and stabs at fabric to explore all the erogenous zones of the body. His clothes are sexy to wear."

This relationship is not dissimilar to the dynamic between Lady Amanda Harlech and designer John Galliano, who, like McQueen, hails from a working-class family (Galliano's father is a plumber; McQueen's is a cabbie). Nowhere, though, is this mix of street influences and grandeur so striking as in McQueen's latest show, which he dedicated to Blow, "for the way she dresses" and for his inspirational weekends spent reclining in her mansion, Hilles, in Gloucester, England. "Issy is like Lucrezia Borgia-the Renaissance Italian duchess who killed off her entire family-mixed with a Manchester fishmonger's wife," says McQueen of his patroness.

With flashing backlit stained-glass windows of Christchurch as a backdrop, blue-blooded girls such as Honor Fraser, Elizabetta Formaggia, and Annabel Rothschild stalked the candlelit, cross-shaped runway; to a soundtrack of Victorian choral music counterpointed by rap and the sounds of gunfire, they rubbed shoulders with hunky male models styled to look like L.A. gang youths. But the show was not just about the clashes of sound and of class: Braid-trimmed hussar jackets were paired with torn lace dresses; and brocade jackets, slit like medieval armor, with pinstriped pants. Denim skirts appeared under jackets stamped with photographic prints of Somalian children and soldiers in Vietnam; towering black wimples accompanied asymmetrically slashed dresses with trains and traditional pantsuits cut in a variety of very untraditional ways. And everywhere, dueling images of the military and the romantic were drenched in the colors of 17th-century Flemish paintings and tapestries.

Such a sensibility smacks at the face of minimalism. "These are clothes for strong women," explains McQueen. "I don't just touch on it, I really go for it." And go for it he will. For McQueen strikes one not as a momentary talent but as a rare visionary armed with a pair of magic scissors.

Text: Sarajane Hoare

Photos: Wayne Maser